In the Studio: The Gang of Five painter on ongoing conversations with his canvases and how the countryside has absorbed the vices of the city

A cramped maze lies between Khâm Thiên street and the Temple of Literature. Slim houses and makeshift shacks hosting all-you-could-possibly-need shops snuggle up to 1960s style apartment buildings in faded Hanoi yellow. One of these houses Hà Trí Hiếu’s studio. But when the painter opens the smaller than norm door in a dark, narrow hallway on the first floor visitors step into an unexpected oasis of light, a seemingly impossible amount of space and a welcoming atmosphere of lingering conversations among friends.

A cramped maze lies between Khâm Thiên street and the Temple of Literature. Slim houses and makeshift shacks hosting all-you-could-possibly-need shops snuggle up to 1960s style apartment buildings in faded Hanoi yellow. One of these houses Hà Trí Hiếu’s studio. But when the painter opens the smaller than norm door in a dark, narrow hallway on the first floor visitors step into an unexpected oasis of light, a seemingly impossible amount of space and a welcoming atmosphere of lingering conversations among friends.

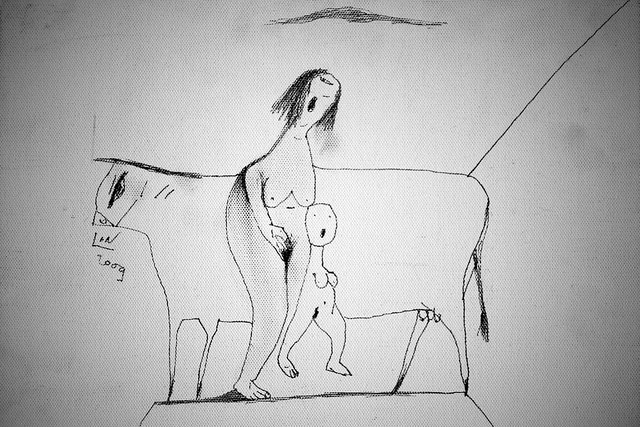

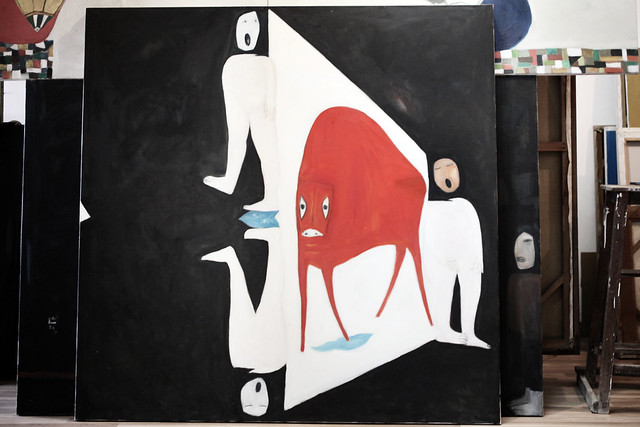

The Gang of Five member has created his signature paintings at this very spot for 20 years. Visitors to Hà Trí Hiếu’s studio are engulfed by his art with paintings from throughout his career filling up all the available space. Buffaloes of all sizes, country girls and self-portraits fill canvases of all sizes that are stacked 10 deep against each wall. A large portion of the other things filling up the rest of the space also bear Hieu’s brush and pen stroke. Intricate sketches on whiskey bottle boxes, CD covers, a single shoe horn and envelopes make this space endlessly fascinating and impossible to tire of.

The top layers of art works are the unusually dark and muted lacquer paintings Hiếu will exhibit at the Heritage Space in the Dolphin Plaza from 5 – 31 July. It is the first time the artist has dabbled with lacquer. But there is no mistaking that this is Hiếu’s work as his ever present muse, the countryside, is present in this latest series as well.

& Of Other Things spent an afternoon with this most charming and amiable of men nosing through his studio, getting excited about the possibility of a Gang of Five reunion exhibition and only leaving with our photographer intact thanks to the attentiveness of our interviewee who made sure the visiting Englishman had a fan pointed at him at all times.

Interview by Đỗ Tường Linh ● Photos by Nic Shonfeld ● Translation by Maia Do and Tabby Chino

&: How did you first get into fine arts?

Hà Trí Hiếu: Fine arts chose me. I was going for architecture before my father told me how into fine arts he was and that he wanted me to go to arts school. He was a portrait painter, but didn’t teach me his painting skills. Instead he took me to Mr Phạm Viết at No. 13 Thuyền Quang street, and that’s where I started learning about fine arts. At first it felt like I was being forced into it, but then I discovered painting to be beyond wonderful and it has become my life-pursuit ever since.

I see art as a flow that pours out from us, and if you are skillful and imaginative enough, you can direct that flow any which way you want. I love what artist Nguyễn Quân once told me “we just keep painting. If in the end people call us losers and there’s nothing we can do about that, that’s fine with me because painting itself is worth it.”

&: What and who inspires you to create art?

Hà Trí Hiếu: My hometown [Hà Tây] remains my most important inspiration. All of my pieces which depict the countryside contain my childhood memories; the people I grew up with, the fields where I went to find left-over rice and potatoes and the spots where I fed cows and buffalos. It is reminiscing, through graphic language. It just feels right when I dwell in these memories, they make me feel light when I transfer them onto my canvas.

I also draw inspiration from poets and writers. The ancient poet, Nguyễn Gia Thiều, for example. Modern poetry interests me too. I like Đỗ Trung Lai’s works. We are actually pretty close and his verses move me. As for literature, there are authors whose works affects me – the contemporary writer Thiệp for example. I’m fond of his early works that comment on some social issues and describe what he taught in the mountains. That’s what I like.

&: You once said “I lived and knew the purest parts of life in Hà Tây.” Is this the reason elements of life in the countryside are found in your early work and are still present in your art today?

Hà Trí Hiếu: This idea of ‘purity’ is what I mean, when I talk about what living in the countryside meant to me. When I was a kid, I lived quite a peaceful life in a quiet village with my relatives, despite the war. It was the purest space and period of time I ever experienced, partly because I was a refugee, not a villager. Had I been a real villager then, I would not view it in the same light, just like a farmer would never see Hanoi the way city residents do.

Like me, I am neither a man from the countryside living in Hanoi, nor a Hanoian visiting his hometown in the countryside. I am both, and each of the two is distinct. I think people in the countryside cannot grasp the way someone who lives in the city feels about the countryside. Just like someone who lives in Hanoi, might not be able to penetrate urban life like a countryman who has travelled a long way to experience the big city does. Each has a unique understanding of the other .

But when I first started drawing my focus was elsewhere. It was only when I graduated and really started working as an artist that I started drawing elements of my relationship with the countryside which was a major part of who I was and it became a topic still present in my art today.

&: How is the countryside today different from the one you knew as a child?

Hà Trí Hiếu: City and countryside are becoming more and more alike. It’s urbanisation. I see karaoke bars and shops displayed exactly as they are in Hanoi. It’s confusing when the city is no longer metropolitan, and the countryside does not differ from the city.

It’s important for a nation when people can tell the city and the countryside apart. That doesn’t mean I do not support development in the countryside, but a rural area has more options in its development than simply copying a city. For thousands of years Vietnamese villages have developed in a way that allowed them to preserve their predecessors’ values. But since the industrial zones appeared in the last ten to fifteen years, the living style of the villagers has completely changed. They pass time with gambling, prostitutes and drugs and seldom spend their money on proper investment. It is all about pleasure.

Newly built houses are copies of Hanoian tube houses that sabotage the old ones that I consider truly beautiful. Had the planners been thoughtful enough, they would have preserved the old architecture.

&: Does this mean the topics of your work are changing too?

Hà Trí Hiếu: In 2008 I started drawing things that at a first glance don’t seem to be related to the countryside. I drew women and called the series “cổng” (gate). That is what they are to me, gates through which people step into the world. I plan to pursue this idea. Though I haven’t exhibited the work, someone who saw it suggested I change the name into something more easily understood. It was suggested that the association people have with “cổng” is literal. People would think of village gates. But for me all gates are the same. And all of us are gates through which we release our identity.

It is all about survival and purity in human lives, but also human obsession. Those [women] are gates leading to life. So I did my research on it and found this human condition is the same in the countryside and in the city and I could combine the two in the same frame. It takes time; and I have only worked on this idea for a few years so I still have a lot to work on. To figure out how to make the paintings beautiful and, at the same time, philosophical.

&: How do you go from an idea to a finished drawing?

Hà Trí Hiếu: Drawing is like a conversation, and it only finishes once you sign the painting. As long as you haven’t signed it, the conversation continues. Even when I’m busy the painting is still on the easel, and the conversation goes on between the artist and the picture. The object is no longer a sketch, but something inside me that I have to focus on to bring it into existence. Just like you and me talking at the moment; it’s hard to focus on other things right?

&: Why did you use cardboard whiskey boxes as canvases in your recent exhibition ?

Hà Trí Hiếu: These whiskey boxes belong to my daily routine, they are part of intimate gatherings between my friends and me. I took what is essentially our litter, added something to it and crossed some things out in order to make a more beautiful thing. They are not really works of art though, that makes them sound too grand.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét